PUBLISHING

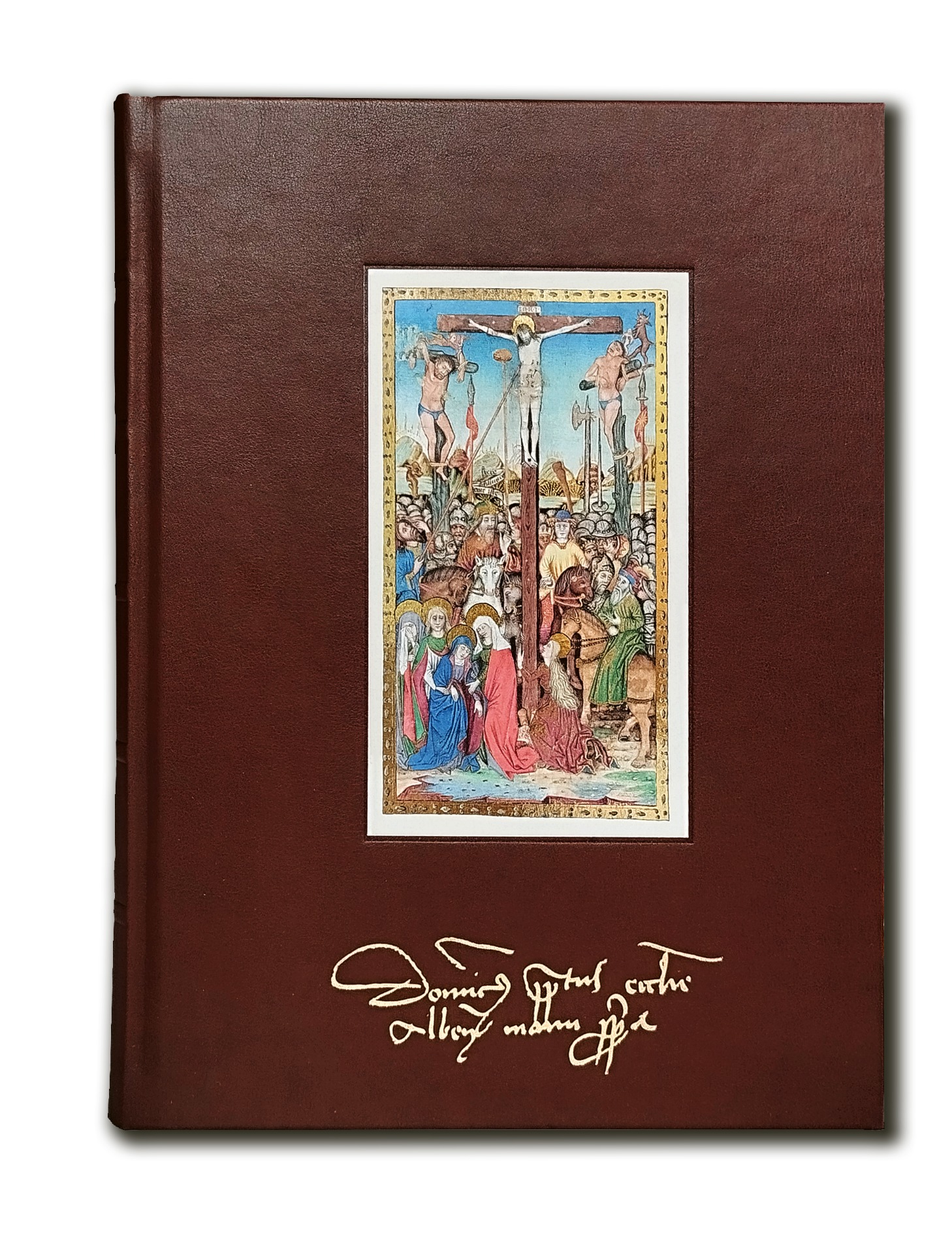

Janus Pannonius:

Sylva Panegyrica ad Guarinum... (1518)

After lots of planning and trials, on October 21, 2008 we published the facsimile of the 1518 "Janus Pannonius: Sylva Panegyrica ad Guarinum Veronensem... Janus Pannonius bishop of Pécs laudatory song to his Veronian master, Guarino" commissioned by the bishop of Pécs for the re-burial of Janus Pannonius. We had to use a bit of a work around since the original cover was missing. We used a contemporary renaissance book's cover from the Klimó Library in Pécs to take its place.

Pécsi Missale (1499)

For the millennial anniversary of Pécs Diocese, we published the facsimile of Missale Pécs first published in 1499.There are only four existing copies of this rarety, unfortunately, all of them incomplete. Luckily with the generous help of the Hungarian National Library, we were able to publish the Missale in its complete form. We take pride in the fact that two of our publications can be found in the personal libraries of Pope Benedict XVI and the president of the Hungarian Republic.At the most prestigious printing competition Pro Typographia this publication was awarded the gold medal being rated 9.9 out of 10.

Published in 2009.

Budapesti Concordantiae caritatis

Our

publication has significant meaning from a cultural history and an art

history perspective; in narrow, professional circles, it used to be

inaccessible, outside of professional circles, the priorly unknown work

can now be a public resource.

Kájoni János: Sacri Concentus

Diversorum Authorum, praesertim Ludovici Viadanae[…]

(Mikháza, 1669)

"To the educated public, the names 'Kájoni Cantionale' and 'Kájoni Codex' may sound familiar. They evoke the figure of János Kájoni, a Franciscan friar active in the second half of the 17th century, whose name is borne by the hymn book he compiled, the musical manuscript that has survived from him. He was a true polymath of Baroque-era Transylvania. In a time of turmoil and crisis — during the final decades of the Turkish occupation of Hungary and the independent Principality of Transylvania — he carried out his work with talent and dedication. His activities were remarkably diverse and wide-ranging. His excellence was highly regarded even by his contemporaries. In the annals of our cultural history, Kájoni has since become a living legend. Even after 350 years, it is worth recalling his figure again and again, delving deeper into his surviving works, and leafing through his notated manuscript."

Ágnes Papp,

Author of the scholarly volume accompanying the facsimile edition

Year of publication: 2015

Nyújtódi/Udvarhelyi kódex (1526-28)

The facsimile edition of this precious manuscript was published in 2018, commissioned by the National Strategic Research Institute, on the occasion of the 425th anniversary of the founding of the Tamási Áron High School in Székelyudvarhely, celebrated on 10 November 2019.

Widely regarded as the most valuable volume of both the high school's collection and possibly of Székelyudvarhely itself, the codex is a Franciscan manuscript of mixed content, intended for use by nuns. It came into being through the binding together of five previously separate sections, each of which had likely been in individual use for some time.

A deeply personal colophon reveals that in 1526, András Nyújtódi, a Franciscan friar originating from the Székely Land, translated and copied parts of the codex for his sister, Judit Nyújtódi, a nun—so that her cell would not lack a book devoted to her patron saint. Through his caring admonitions addressed to nuns and his interspersed explanatory notes, the texts take on a distinctly individual and original character, blending translation, commentary, and pastoral intent.

The second part of the codex (pp. 233–312), originally an independent unit, bears a separate colophon indicating it was copied in Tövis in 1528, likely by Judit herself, who is also presumed to have been its owner. The colophons in the first two parts also confirm Judit Nyújtódi as the original possessor of the manuscript.

The codex's Renaissance leather binding, characteristic of mid-16th-century Transylvania, provides material evidence that the originally separate parts had been unified into a single volume already by that period.

The manuscript's history after the 16th century remains obscure. However, Imre Lukinich, based on pen-drawn monograms of Jesus and Mary affixed to the inside of the front cover, hypothesized that the codex may have once belonged to the Jesuit College of Székelyudvarhely.

Later provenance is clarified by a handwritten note from Dániel Fancsali, a parish priest of Gyergyószentmiklós and later teacher and headmaster in Székelyudvarhely, confirming that he owned the codex in 1810. It was from his library that the manuscript found its way into the collection of the Catholic Gymnasium of Székelyudvarhely, where it was eventually rediscovered in 1876 by Sámuel Szabó, a teacher at the Reformed College in Kolozsvár (Cluj).

Published in 2018.

Album Gymnasii Udvarhely (1689)

Published in 2018.

Evangeliary

In 2019, I was deeply honored to be entrusted with the creation of the Evangelary used during the Holy Mass celebrated by His Holiness Pope Francis in Csíksomlyó. This sacred volume was prepared specifically for the occasion, and its commission remains one of the most meaningful moments of my professional and spiritual journey.

Kálmáncsehi-breviary

This manuscript is one of the most resplendent relics of late medieval Hungary. Its illuminated folios originate from a codex once belonging to Domonkos Kálmáncsehi, provost of the coronation church in Székesfehérvár, now preserved far from its homeland—in New York. Written on parchment and richly decorated, this manuscript served the high-ranking cleric in the fulfillment of his liturgical and devotional duties. The first part is a breviary—a priest's book of daily prayers—while the second constitutes a missal. A liturgical calendar was placed at the beginning, recording the feasts and structure of the ecclesiastical year. Its small format and the combination of two distinct texts within a single volume suggest that Kálmáncsehi Domonkos used this codex primarily during his travels.

The manuscript carries the message of a pivotal historical moment. At the end of the 15th century—especially in the 1480s—Hungary witnessed a unique decade during which past and future converged. Centuries of tradition and the aspirations of generations found expression in the resounding overture of the Hungarian Renaissance. Under the reign of King Matthias Corvinus (1458–1490), Vienna was conquered, royal residences were built, and the renowned Bibliotheca Corvina was established—just a few of the era's defining achievements. The prevailing cultural model and source of inspiration was the Italian Renaissance. Architects, sculptors, carpenters, illuminators, bookbinders, musicians, astronomers, jurists, historians, and other humanists arrived in Hungary, leaving a lasting imprint on the nation's intellectual and artistic development. Much of what was initiated in this era would shape the cultural history of Hungary for centuries to come.

The royal book workshop in Buda served not only the needs of the king's library but also produced manuscripts for high-ranking clerics. The breviary of Kálmáncsehi Domonkos was likewise produced in this atelier. Its decoration is especially valuable, as many of its motifs derive from volumes in the royal collection, which at that time bore the unmistakable imprint of Italian illuminators. Yet upon closer inspection, the pages reveal elements of Central European Gothic book painting alongside the Renaissance ornamentation: long, slender, pointed leaves curl in elegant tendrils, and the breviary's initials display a consistent Gothic style. In these folios, we witness a natural synthesis of the Italian Renaissance and local artistic tradition.

The codex survived the devastation of medieval Hungary and the tumultuous centuries that followed with remarkable fortune. By 1782, it was recorded in the Cistercian Abbey of Viktring, near Klagenfurt, before entering the Library of the Princes of Liechtenstein in Vienna. By 1948, it had surfaced in New York, circulating among private collectors. Ultimately, in 1963, the manuscript found its present home in the collection of The Morgan Library & Museum. The publication of a facsimile selection from the codex is significant not only because of its scholarly value, but also because it makes this once nearly inaccessible manuscript available to a wider audience.

The codex includes a handwritten note by its owner and commissioner, Domonkos Kálmáncsehi, stating the date of its copying and his own age at the time. This personal inscription lends the manuscript an unexpected intimacy that continues to resonate with modern readers.

Published in 2021

Dominicus Kálmáncsehi's Prayer Book

(Buda, 1492)

Domonkos Kálmáncsehi, Provost of the Church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Székesfehérvár—the royal coronation basilica—was one of the most prominent figures of King Matthias Corvinus's court. According to the Italian humanist historian Antonio Bonfini, the king entrusted this high-ranking prelate, noted for his eloquence and charismatic personality, with diplomatic and financial responsibilities. Yet for posterity, Kálmáncsehi is remembered above all for his bibliophilia.

Of the known codices once in his possession, three are now held in foreign collections. Recognizing their cultural significance and inaccessibility to Hungarian researchers and the general public, the National Strategic Research Institute has made it a mission to produce facsimile editions of these distant treasures—thus reclaiming these precious national relics for broader appreciation and scholarly engagement.

This richly decorated codex, reminiscent of a jewel box, holds a wealth of historical and artistic curiosities. Its content reveals a unique interweaving of Hungarian and Austrian liturgical traditions, providing insight into the diverse devotional practices of the period. Unusually, we know the name of its scribe—Stephanus de Cachol, a Franciscan friar—who identified himself within the manuscript.

The ornamentation of the codex serves as an exceptional synthesis of the illuminated styles that once adorned the volumes of the famed Bibliotheca Corvina. It encapsulates the artistic tendencies developed in the royal scriptorium of Buda during the final years of King Matthias's reign. At the same time, it offers a rare glimpse into the transformation of court art in the wake of the great patron's death.

As such, this illuminated manuscript is not only a devotional artifact but a crucial primary source for the study of Renaissance art in Hungary.

Edina Zsupán

Year of publication: 2023

Cronica Hungarorum

(Buda, 1473)

"Finita Bude anno Domini MCCCCLXXIII in vigilia penthecostes: per Andream Hess" — "Completed in Buda in the year of our Lord 1473, on the eve of Pentecost, by András Hess."

With this closing sentence, the history of Hungarian printing begins.

The Chronica Hungarorum, a small folio volume consisting of seventy leaves (amounting to 133 printed pages), survives in only ten known copies worldwide. Its creation marks the advent of the printing press in the Kingdom of Hungary. Yet, little is known about its printer, András Hess. Based on his name, he is presumed to have been of German origin, possibly trained as a journeyman at the Lauer press in Rome. He likely arrived in Buda in the late spring of 1471, at the invitation of László Kárai, provost of Buda, and brought with him typefaces acquired in Italy to produce Hungary's first printed book.

Due to the destructive effects of later wars, no archival documents survive regarding the foundation or operation of Hess's printing workshop. Thus, all that is known derives solely from the book itself. We learn that the master printer completed his work on June 5, 1473, roughly two years after his arrival.

It is now considered a near certainty—supported by multiple converging sources—that the spiritual architect of Hungarian printing was Archbishop János Vitéz of Esztergom, one of the greatest patrons of Renaissance culture in the region. Hess may have been drawn by the promise of privileges, financial backing, and guaranteed commissions, all in service of founding an independent press in Buda.

However, political winds shifted dramatically in the second half of 1471. Archbishop Vitéz, breaking ranks with the crown, supported the Polish prince Casimir, son of King Casimir IV, in a claim to the Hungarian throne. By early 1472, the archbishop had fallen from power, placed under house arrest in Esztergom, where he remained until his death that August.

These events left Hess in a precarious position: the original printed dedication, addressed to Vitéz, had become politically untenable. He was forced to choose: either his book would never be published, or he would revise the dedication. He chose the latter. The new dedicatee became László Kárai, who may have also provided financial support in early 1473. In Hess's own words:

"Without you, I could not have undertaken or completed the task I set for myself."

The text of the Chronica Hungarorum is a composite historical narrative, drawn from various medieval sources and codices of the 14th and 15th centuries. The final section, whose author remains unknown, recounts the history of Hungary from the death of King Louis the Great (1382) to Matthias Corvinus's Moldavian campaign (1468)—a span of eighty years condensed into a brief epilogue.

This abrupt summary covers nearly a century in just four pages, with striking imbalances in historical emphasis: Emperor Sigismund, who ruled for nearly fifty years, receives scarcely more attention than Albert of Habsburg, who reigned less than two. As for King Matthias, the chronicle touches only briefly on his coronation (1458), the recapture of Jajca (1463), the recovery of the Holy Crown (1464), and the campaign against Moldavia (1468).

The chronicle ends abruptly, omitting the final four years (1469–1473) of Hungary's history. This silence likely reflects deliberate restraint: the sensitive events of 1471–1472, including the political conspiracy, the Polish incursion, and the downfall and death of Archbishop Vitéz, were still too recent and too contentious to be openly addressed.

Gábor Farkas Farkas

Year of publication: 2023

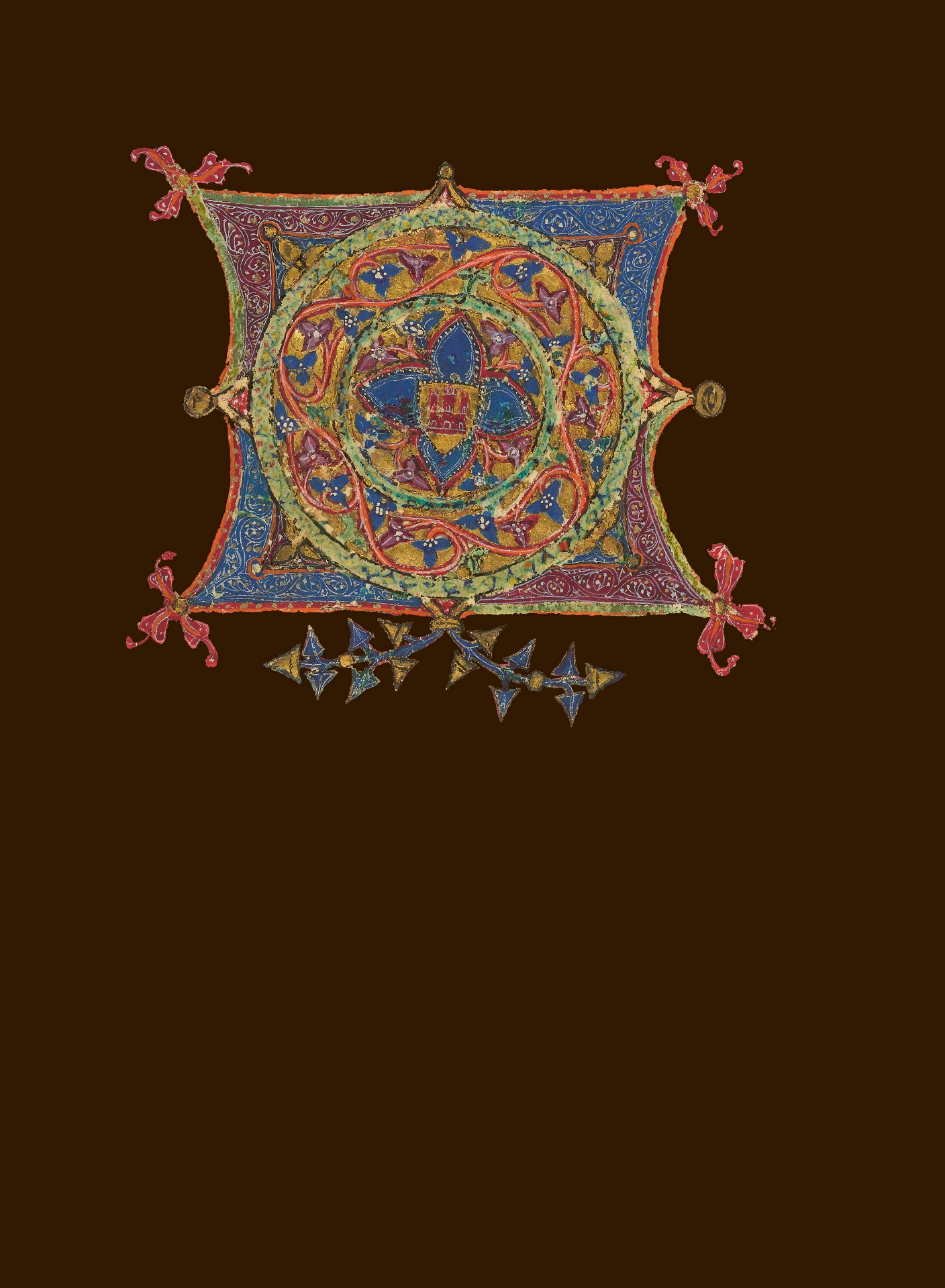

Chronicon Pictum

(Chronica de gestis Hungarorum, also known as the Képes Krónika)

The Illuminated Chronicle—a Latin parchment manuscript titled Chronica de gestis Hungarorum, or "Chronicle of the Deeds of the Hungarians"—is one of the most richly decorated and celebrated relics of medieval Hungarian historiography. Preserved today in the National Széchényi Library (Cod. Lat. 404), the codex was likely compiled around 1358 by Márk Kálti, canon and guardian of the Basilica of the Assumption in Székesfehérvár, at the commission of King Louis the Great (Lajos I), to serve as a princely chronicle for the monarch.

Following the medieval historiographical conventions of the time, the narrative begins with biblical origins, moves through Hun history, and continues up to November 1330. The chronicle, however, remains unfinished, with the text breaking off abruptly mid-sentence.

What makes the manuscript truly exceptional is its rich visual program: each chapter is accompanied by narrative miniatures, many of which portray iconic figures such as Attila the Hun, Saint Stephen, and an abundance of images dedicated to King Saint Ladislaus (László). Lavish initials and marginal ornamentation further enhance the volume, marking it as one of the most distinguished examples of Gothic book illumination in medieval Hungary.

Among the most striking features is the opening page, where King Louis I is depicted enthroned, holding the sceptre in his right hand and the globus cruciger in his left, both hands adorned with white gloves—a powerful symbol of royal dignity and sacred authority.

Another notable miniature (f. 11r) illustrates the Hungarian Conquest of Pannonia, while folio 21r depicts Saint Stephen at the center, his head encircled by a radiant halo, standing in triumph over Kean, a Bulgarian-Slavic ruler. On folio 36v, Prince Ladislaus is shown in fierce combat with a Cuman warrior, a theme central to his legendary cycle.

Thanks to its artistic unity, historical ambition, and royal patronage, the Illuminated Chronicle stands not only as a literary monument but also as a visual testimony to the dynastic memory and political ideology of 14th-century Hungary.

Gábor Sarbak

Planned year of publication: 2025

The Philostratus Corvina

The Philostratus Corvina is among the most distinguished volumes of the Bibliotheca Corvina, the Renaissance royal library of King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary (1458–1490). It contains the works of the ancient Greek sophist Philostratus, translated into Latin by the court historian Antonio Bonfini.

Produced in Buda in the late 1480s, shortly after the capture of Wiener Neustadt (1487), the manuscript is remarkable not only for its aesthetic refinement but also for its deep connection to the courtly environment in which it was created. It perfectly reflects the representational ideals of the Hungarian royal court and stands as eloquent testimony to the formation of the royal library as a tool of dynastic prestige and cultural ambition.

The manuscript's iconographic program serves first and foremost to glorify Matthias's military victories, particularly his conquest of Wiener Neustadt, but it also celebrates his patronage of the arts and sciences. Its visual language draws heavily on classical Roman imperial imagery; King Matthias himself is portrayed in the style of Roman imperial medallions, aligning him with the legacy of the Caesars.

Uniquely, the codex's table of contents contains the only known contemporary reference to the royal library under its now-famous name: "Corvina Bibliotheca".

The volume's binding was completed during the reign of King Vladislaus II (Ulászló), Matthias's successor. Its reputation soon spread among the Viennese humanist circle, and one of its members, Johannes Gremper, ultimately acquired the manuscript—receiving it directly from King Vladislaus II. The codex later passed into the hands of the historian and humanist Johannes Cuspinianus.

Following the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the Philostratus Corvina was finally returned to Hungary in 1933. Since then, it has been preserved in the National Széchényi Library.

Edina Zsupán

Year of publication: 2024

The Pray Codex

The Pray Codex—a 12th-century parchment manuscript and one of the most treasured holdings of the National Széchényi Library (MNY. 1.)—stands as one of the most important liturgical monuments of medieval ecclesiastical culture in Hungary.

Formally classified as a sacramentary, the manuscript contains the texts of the Holy Mass, arranged according to the liturgical calendar. In addition to these core contents, the codex also preserves several shorter writings, including a liturgical calendar and a brief treatise on ritual practices.

It is within the latter—specifically in the appendix to the funeral rite—that we find one of the most momentous records in Hungarian cultural history: following the Latin funeral oration, there appears a sermon in the Hungarian language, known as the Funeral Sermon and Prayer (Halotti beszéd és könyörgés), found on folio 136r. This is the oldest extant continuous Hungarian text, and as such, holds a foundational place in the history of Hungarian literature.

From a historical standpoint, the manuscript also includes the Annales Posonienses (Annals of Pozsony)—brief historical notes that offer valuable insight into the events of the Árpád era.

The codex further preserves colored pen drawings depicting the Crucifixion and Resurrection of Christ (fols. XXVIIr–v, XXVIIIr), which constitute important relics of medieval Hungarian religious art. Equally noteworthy are the Gregorian chant notations, which offer a rare glimpse into the musical culture of the medieval Hungarian Church.

Through the convergence of language, liturgy, history, and visual art, the Pray Codex emerges as a uniquely layered witness to 12th-century Hungarian spiritual life and cultural heritage.

Gábor Sarbak

Year of publication: 2025

The Kaufmann Haggada

Perhaps the most renowned manuscript of the Kaufmann Collection, housed in the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, is the codex marked A 422, known as the Kaufmann Haggadah. Originating in 14th-century Catalonia, this exquisitely illustrated volume contains the prayers, poems, and narrative passages recited during the Passover Seder, the family ritual held on the eve of Pesach—the Jewish festival commemorating the Lord's "passing over" and the liberation from Egyptian bondage.

During the High and Late Middle Ages, particularly between the 11th and 15th centuries, it was not uncommon for Haggadot to be produced for private, domestic use. The Kaufmann Haggadah bears clear signs of such intimate engagement: its well-worn pages speak of a beloved household treasure, repeatedly opened, shown, and shared. One can easily imagine the head of the family—proudly turning its pages for his children, not only on the appointed night of the festival, but at other times as well—gathering the family around after dinner to marvel at the splendid and captivating illustrations.

Children hold a central place in the Passover ritual, and what better way to ignite and sustain a child's imagination than with images of such vibrancy, mystery, and wonder? The Kaufmann Haggadah thus serves not only as a liturgical guide, but as a tool of memory, education, and emotional connection—bridging generations through beauty and faith.

Beyond its religious significance, the manuscript is an invaluable artifact of cultural history and ranks among the masterpieces of medieval Jewish art.

Gabriella Séd-Rajna

Planned year of publication: September 2025